WASHINGTON — The U.S. Supreme Court is set to decide this week whether Louisiana continues to have two districts, rather than one, designed to give Black candidates a reasonable chance of election to the U.S. House.

The nine justices plan to discuss Callais v. Landry behind closed doors Friday. They will decide whether to hear Louisiana’s redistricting case or send it back to a three-judge panel that in April dismissed the Legislature’s map that allowed two minority-majority congressional districts.

“I can't speculate on what they're going to do,” said state Sen. Royce Duplessis, D-New Orleans, who is elbow-deep in efforts to create a second minority-majority district. “It was the will of the Legislature to have two majority Black districts.”

State Rep. Kyle Green, a Marrero Democrat closely monitoring the litigation, echoed a legal scholar predicting: “The Supreme Court is likely to send the case back to the three-judge panel with instructions.”

If so, the long and winding road over Louisiana’s second minority-majority congressional district might continue with a second Black district into 2028 — two years before the next U.S. Census.

Though the last Census counted a third of the state’s population as Black, the Louisiana Legislature initially approved a map in 2022 ensuring the election of five White Republicans to the state’s six-member House delegation.

After a legal challenge by Black voters, Chief U.S. District Judge Shelly Dick, of Baton Rouge, found two minority-majority districts warranted under the Voting Rights Act. She gave the state until January to draw new maps with two Black “opportunity” districts or the courts would.

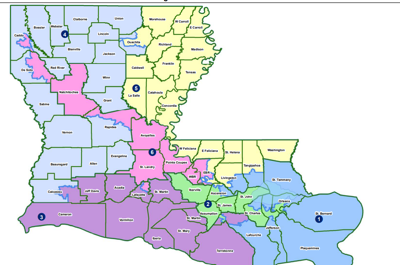

In his first act as governor, Jeff Landry called the Legislature into special session to create those two districts, which it did in January. Senate Bill 8 linked Black neighborhoods from Baton Rouge to Shreveport to create a new 6th Congressional district.

A dozen voters, the Callais litigants, challenged SB8 by arguing the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause forbids districts drawn on a racial basis.

The 5th Circuit named a three-judge panel to consider the case. In April, two of the three judges threw out the Legislature’s January map.

The state and the Black voter litigants received an emergency pause from the Supreme Court, which asked for arguments on why the nine justices should sort out the conflict.

Callais’ lawyers argued that until Dick’s order, Attorney General Liz Murrill had defended the Legislature’s original map, saying Louisiana’s Black population lived too far apart to require a second Black majority district under the Voting Rights Act.

“The State admits that the two-district racial quota was set first, and only later did politics determine which one of the five Republicans’ seats would be sacrificed to create the second Black-majority district,” Callais argued.

Callais filing with US Supreme Court

Murrill countered the state faced the prospect of the courts drawing the maps rather than legislators.

“The Legislature did not eliminate a Republican-performing district merely for political purposes; it did so because the courts forced the Legislature to create a second majority-Black district,” Murrill wrote.

State's filing with US Supreme Court

The Legislature had an alternative map that better met the Voting Rights standards of compactness, fewer split parishes, and compatible needs. That configuration went north of Baton Rouge toward Monroe and compromised the electability of Rep. Julia Letlow, R-Start, said Victoria Wenger, a counsel for the Black litigants with NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc.

Louisiana legislators instead chose a map “to have (Rep.) Garret Graves (R-Baton Rouge) to be the one on the chopping block instead of Julia Letlow,” she said.

Robinson Intervenors filing with US Supreme Court

In May, a 6-3 Supreme Court majority found the South Carolina General Assembly’s political reason for removing 62% of the Black voters out of a purple district and thereby protecting a Republican congresswoman’s reelection trumped racial reasons.

The Callais litigants want the high court to affirm the three-judge panel’s decision to return to a single Black majority district without further argument, said Paul Loy Hurd, a lawyer for Callais.

But should the high court ask the Louisiana panel to consider its South Carolina decision, the results would show that courts should intervene to block racial gerrymandering. The South Carolina decision “directly repudiates Louisiana’s desperate plea that courts should abruptly end their decades-long commitment to remedy racial gerrymanders,” Hurd said.

Michael Li, with the Brennan Center at New York University and one of the nation’s leading experts on redistricting law, says his best guess is that the Supreme Court will order the three-judge panel in Louisiana to consider politics versus race considerations in light of the court’s South Carolina decision. That would give the high court a better record for balancing the strictures of Voting Rights and Equal Protection in Louisiana's case.

“The Supreme Court will have the ultimate word. But I think that’ll take a while,” Li said. “So that probably leaves the (two Black majority district) map in place for the 2026 election.”