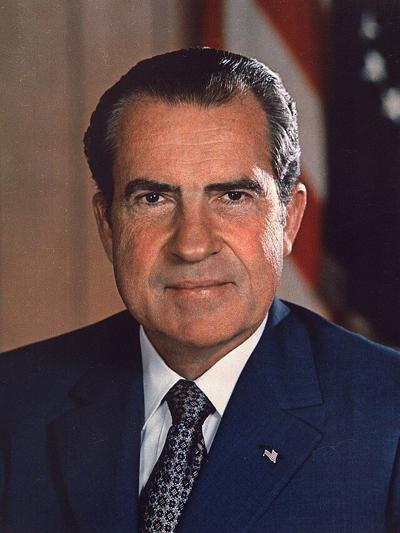

Although grown-ups are supposed to shield children from scandal, my parents didn’t bother sending me out of the room as news of the Watergate cover-up forced President Richard Nixon from office 50 summers ago this month — on Aug. 9, 1974.

I was only 10 years old, not likely to grasp what was happening, anyway. The older people around me didn’t seem to understand Watergate much better than I did. Life had changed for us the summer before as the U.S. Senate held televised Watergate hearings from May through August 1973. Lawmakers wanted to learn what Nixon knew about a break-in at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate building in Washington.

Both of my grandmothers, who fretted about having their afternoon soap operas preempted by the hearings, weren’t as riveted by questions of constitutional order as the senators who droned through our days. Those long Louisiana afternoons of my childhood now felt even longer.

Watergate jumbled my routines, too. Summer for me had meant late afternoon matinees on the television, which usually broadcast monster flicks like “Frankenstein” or “The Invisible Man.” Instead, the most ominous part of my summer was testimony by Nixon associates John Dean and Alexander Butterfield. The tone of the hearings, which combined scolding homilies and the narrow parsing of fact, reminded me of school, a drudgery that summer was supposed to relieve.

In those days before 24-hour cable news, we didn’t expect the world to sit in our living rooms from dawn to dusk. Except for assassinations and moon landings, current events confined themselves to the newspapers and broadcasts at the top and bottom of the day. But Watergate made us feel as if the news had spilled its banks somehow, flooding every hour with urgency.

With little but Watergate on TV all summer, I escaped outside — turning over rocks, playing with the dog, dousing dragonflies with my water pistol. I trace my interest in the outdoors to that strange season when a drought of decent television programming nudged me to think about trees, birds, and grass instead. One August afternoon in 1974, I came inside for a drink of water and sensed that the mood in our den had turned glum. On our big Zenith console, I could see Nixon waving goodbye as he climbed into a helicopter. My grandmother Tucker, hunched in her recliner, fished a handkerchief from her pocket and dabbed her eyes.

What she was mourning, I’d later understand, was a break in the familiar rhythms of national life.

Five decades later, I remember her capacity that fateful day to be shocked by political turmoil. Civic life has hardened a lot since then, and we’re not as shaken by the moral lapses of our leaders as we used to be — a half a century since I saw my grandmother weep over Richard Nixon’s exit, that capacity to be shaken seems the biggest loss of all.

Email Danny Heitman at danny@dannyheitman.com.